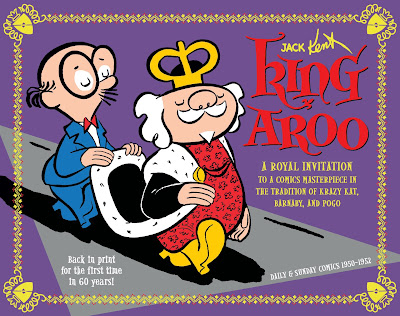

Jack Kent's King Aroo

One of the finest comic strips of all time has finally been reprinted after decades of unavailability.

Interview with Bruce Canwell

By Gentle Jones

The land of Myopia does not appear on most maps, as this tiny kingdom is only an acre in size. The supreme crown ruler, the delightful yet dotty King Aroo, is accompanied by his Prime Minister Yupyop. Together they sail through the days with a cast of quirky animals as wacky and well-spoken as those found in Walt Kelly's Pogo.

Though Jack Kent's King Aroo daily comic strip ran in as many as a hundred American newspapers and in many major cities from 1950 through 1965 it has remained obscure. Rarely reprinted and never before completely collected, only a select group of fans have continually sang praises of the enchanting dialogue and Kent's wonderful brushwork.

King Aroo is an entirely charming strip, at its best the work stands among the greatest of the dailies: Krazy Kat, Pogo, Li'l Abner, Bloom County. That it has become nearly forgotten is tragic, for each panel is playful and the adventures are timeless.

Jack Kent went on to gain much acclaim with his children's books after King Aroo's run, yet this daily strip is surely his magnum opus. Though Kent had no formal training, he was a voracious reader of comics and corresponded with the greatest illustrators of his time, such as George Herriman and Milton Caniff, and amassed an impressive collection of their original artwork, which he studied as he honed his craft independently. At the age of 30 his first strip, King Aroo, was picked up by the McClure syndicate, and now six decades later the Library of American Comic republished this classic strip from the beginning for the first time.

The Library of American Comics (LOAC) is published by IDW (who are best known for the graphic novel 30 Days of Night) and has already reprinted collections of daily strips from Little Orphan Annie, Dick Tracy, Terry and the Pirates, Bringing Up Father, and more.

Gentle Jones: Where do you think King Aroo ranks among the pantheon of the recognized newspaper strip classics?

Bruce Canwell: Up to now King Aroo has been a cult favorite, a shrinking-violet cousin to Krazy Kat and Pogo, much beloved by a small group lucky enough to have sampled the strip in places like Bill Blackbeard’s Smithsonian Book of Newspaper Comics. Jack Kent's fame as a children’s book author far eclipsed his notoriety as a cartoonist.

Of course, King Aroo deserves a larger audience, with much more visibility than it's received down through the years, and Jack Kent's talents should be recognized alongside those of artists like George Herriman, Crockett Johnson, Sparky Schulz, or Bill Watterson. By adding King Aroo to The Library of American Comics, we hope to do our part to help find that larger audience for the strip and to help achieve that modern-day recognition for its creator.

In these days when there is so much discussion of "appropriate" material for children, King Aroo is an exceptional read for all ages. Not in a corporately-sanitized, squeaky-clean way, but as an example of a creator who knows how to entertain without being salacious or striking a sensationalist tone. Young kids enjoy Kent's charming artwork and the funny animals -- teenagers enjoy the sophistication of the story-lines -- and adults get pleasure from the cleverness of the wordplay. As much as King Aroo draws deserved comparisons to Krazy Kat and Pogo, I find it most closely related to Jay Ward's Bullwinkle and Rocky TV show. They both appeal to a wide range of age groups while never talking down to anyone in the audience. That's a tough trick to pull off, but Jay Ward and his people did it in Bullwinkle, while Jack Kent did it equally well in King Aroo.

Gentle Jones: How widely circulated was King Aroo at its peak?

Bruce Canwell: By Kent's own count King Aroo never ran in more than one hundred newspapers, though it appeared in many major metro areas: New York, Chicago, Houston, Kansas City. Jack Kent originally sold King Aroo to the McClure Syndicate, which was a giant in the first half of the 20th Century, but a shadow of itself by the early 1950s (in fact, McClure merged with the Bell Syndicate during King Aroo's initial run and couldn't even come out top dog in the new structure, which was named the Bell-McClure Syndicate). McClure didn't have a large enough sales staff to reach into the suburbs and rural areas of the country, focusing instead on the big cities. That's one of the reasons King Aroo hasn't been widely known -- it never achieved the widespread newspaper penetration achieved by strips such as Beetle Bailey or B.C.

But most important of all, McClure was able to place King Aroo in the San Francisco Chronicle. After Kent and McClure went their separate ways one of the Chronicle's editors, Stanleigh Arnold, single-handedly provided an outlet for Jack Kent to remain in Myopia, telling entertaining stories.

Gentle Jones: How did you first discover King Aroo?

Bruce Canwell: Remember that small group I mentioned awhile ago? I’m a member of a small group within that small group, because I didn’t come to King Aroo via The Smithsonian Book of Newspaper Comics; I took an alternate route.

In the 1980s, Fantagraphics published a magazine called Nemo, devoted to classic comic strips. I was a devoted reader of the title and its 21st issue, published in 1986, cover-featured King Aroo with a brief history of the strip plus a long reprint of a story sequence from the 1960s. I was immediately won over, and working on our own King Aroo series has only caused my admiration to grow, both for Jack Kent's talents and the cleverness of his creation.

Gentle Jones: How much demand are you finding for these collected newspaper dailies?

Bruce Canwell: Market research shows the core LOAC audience is composed of serious comics collectors and younger artists who are interested in seeing and learning from the work of master cartoonists from previous generations. Some strips, such as Bloom County, also have a number of readers who remember when the series was running in their daily newspaper; those folks want the nostalgic pleasure of re-reading those fondly-remembered strips in a collected edition. We set our print runs accordingly and when a book sells out, we're prepared to go back for a second printing, as we did with our first Terry and the Pirates release

Gentle Jones: Which term do you prefer: graphic novel or comic book?

Bruce Canwell: As I've grown older, I often find myself using a term from my Dad's boyhood: "funnybooks." (I can hear the gasps now!)

Seriously -- this is something I don't give a whole lot of thought. It's like when someone asks me, "What kind of music do you like?" My reply is, "I like good music." Which invariably spurs another question: "What's the difference between good music and bad music?" To which I say, "Good music is stuff you like, and bad music is stuff you don't." Rock, pop, jazz, r&b, fusion, country, folk, swing, hip-hop, soul -- it doesn't matter to me. Same with comics -- I like good comics, whether it's Eisner's To the Heart of the Storm (packaged from the outset as a "graphic novel") or Fantastic Four # 51 (which is clearly a "comic book," even when it's reprinted in a $99 Omnibus volume).

At the end of the day it's all comics, and the collateral terms we use just references the packaging. Seems to me life's too short to get hung up on packaging.

Gentle Jones: I've read some about your background, its an interesting story. How did you parlay writing comic reviews into writing Batman and publishing gorgeous collections of comics?

Bruce Canwell: Actually, I didn't parlay one gig to the other -- unfortunately! Every major assignment I've landed has its own genesis, largely unrelated to what has preceded it. The "Gauntlet" assignment did give me an "in" with the Batman editors that lead to my "Huntress" story in Batman Chronicles # 14 and a Batman-vs-Penguin fill-in issue of Batman penciled by the wonderful Jim Aparo (which still resides in the DC inventory, unpublished, alas), but that's about all the "parlaying" I've ever managed.

The story of how Dean Mullaney and I came to launch The Library of American Comics has never really been discussed in any detail, though, so this might be a good chance to tell that story . . .

In our younger days, back in the 1970s, Dean and I were both regulars in the letters pages of many Marvel Comics titles. Dean read my letters and I read his, yet we had no direct communication with one another. As the decade wound down, Dean decided to launch Eclipse Enterprises, using names and addresses from those Marvel letter columns as one way to build his mailing list as he solicited orders for his first book, Don McGregor and Paul Gulacy's Sabre. I was growing bored with comics at the time I received Eclipse's solicitation letter in the mail; I was geared up for something new and different. I admired McGregor and Gulacy's work, so despite the unheard-of price of $5.00 for a comic (*gasp!*), I said, "Why not?" Aside from Dean receiving an envelope with my money and him sending me a copy of Sabre after it was printed -- which I own to this day, by the way -- we still had no direct contact.

Flash forward to 2005. Dean had been away from comics since Eclipse folded, more than a decade before. I got shut out of more comics work around 1999, when the business went through one of its periodic nosedives (casualties of the Marvel bankruptcy and its aftermath during this period were two editors with whom I had been working, and very cool Nick Fury and Deathlok the Demolisher series I had been developing). I was writing a bi-weekly column for a now-defunct website, something fun to keep my hand in, and I devoted a column to how Sabre revived my flagging interest in comics at a time when I could have easily walked away from the medium. Still no contact between Dean and I -- but that would soon change . . .

For a variety of reasons, Dean was thinking of getting back into comics. He started by googling Eclipse, found my column on Sabre, and used the e-mail address in my by-line to drop me a note thanking me for the kind words. He also said, "Aren't you the guy who wrote almost as many letters to Marvel as I did, back in the day?" So we started off by just swapping "letterhacking" war stories and comparing notes as Dean went back to his roots and re-read things like the Ditko Doctor Strange for the first time in a looooong while.

It didn't take long to shift our gaze from the past to the future: we started talking about projects we might do together. We both love Terry and the Pirates and Dean suggested reprinting it in hardcover. He had the contacts to put together The Library of American Comics (LOAC) and set up the arrangement between LOAC and IDW, which has been a very welcoming and supportive partner. We had so much fun on Terry we also launched Little Orphan Annie, then Scorchy Smith & The Art of Noel Sickles.

The LOAC line has blossomed from there, and while it's a lot of work to produce these books, Dean and I have plenty of laughs, too. We've got together several times, both for business reasons (research at The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum) and for pleasure (we're both baseball fans, so we went to Fenway Park to see the Red Sox retire Johnny Pesky's uniform number -- and to take in the ball game, too, of course!).

Gentle Jones: Is it true that you are reprinting Li'l Abner in its entirety? (!!)

Bruce Canwell: Get ready to bite off big chunks of the Dogpatch Ham, because that is 100% true! Li'l Abner Volume 1 is a spring release, with Volume 2 out in the very early autumn. I'm writing the text features for the series, Denis Kitchen -- who serves as agent for the Capp Estate -- has written a personal and insightful introduction to our first volume, and we'll be presenting the dailies as well as the never-before-reprinted Sunday pages in each book of the series. Throughout its existence, Al Capp ran separate plots in the dailies and Sundays, so there are whole story-lines many Abner fans have never been able to read -- until now.

It's very exciting to be able to bring Li'l Abner back into print and to put Al Capp's unique satirical voice in front of an audience once again. During my research I found the absolutely perfect quote, from John Updike, with which to launch our Abner series; it leads off my text feature. Look for it in Li'l Abner Volume 1 and see if you don't agree.

Gentle Jones: How do you feel newspaper comic strips impacted American entertainment and story telling over the past century?

Bruce Canwell: There are fewer than a dozen art forms that are native to America. Some quibble over the exact number -- Harlan Ellison has one number in mind, while noted critic Gilbert Seldes had another -- but no one doubts that comics is one of that small, select group. The combining of words and pictures in a sequential format to tell a story or make a point is a uniquely American tradition. Sharing that tradition with a modern audience is one of the absolute delights of working on LOAC books.

In the early years of the 20th Century comics were an incredible drawing card, because America was a society of readers. Television was scarcely a dream, movies were still silent, not every household had a radio set . . . but in big cities and rural towns, people read newspapers, whether they bought them at stores or newsstands or leafed through them at the public library. Comics were big, bold, colorful, and eye-catching -- how could a nation of readers ignore them?

Over time, radio became ubiquitous, sound came to the motion pictures, the phonograph brought music into the home, then along came television. Newspapers squeezed the dimensions of the comic strips and the nation increasingly turned away from one of its favorite art forms . . . but the love affair has never died. The strip names shift over time -- from Li'l Abner to Peanuts to Calvin & Hobbes -- but there has continually been at least one "beloved" strip that resonates within the national consciousness.

And strip characters still keep popping up in different media -- in recent years the Sci-Fi Channel (now "Syfy") tried a new spin on Flash Gordon even as a road show theatrical production of Annie has been touring the country. Hollywood is now full of actors, directors, and executives who grew up on comics, and who knows? Thanks to The Library of American Comics re-introducing some of these comic strips to 21st Century audiences, some day a big-budget Rip Kirby feature film or an animated King Aroo movie will be coming to a theater near you.

Bottom line: Comic strips have had a tremendous effect on pop culture and on American society in general. It’s a pleasure to help keep that wheel rolling on.

Comments